Is our movement too focused on the 'nightmare' rather than the 'dream'?

A look at how our communications can shift the narrative from welfare to freedom...

To create a better world, we need to tell more stories about what’s possible and how animal freedom can benefit all of society, not just our animal cousins. After all, we can only bring into existence what society can imagine and believes is possible. This is the work of narrative change, and it’s why it’s always been foundational to social change. But is the way we’re communicating our cause limiting our movement’s ability to really make progress towards animal freedom?

How do ‘outsiders’ view the animal freedom movement?

At an event last year, we asked a social justice communications expert for her honest thoughts on the animal freedom movement. As someone who’s not vegan and hasn’t worked extensively on animal-related causes, we wanted her perspective as an 'outsider' on how we communicate our issue. Her answer was a bit of a wake-up call…

“Your tactics remind me of the anti-abortion movement. Both of you use graphic, sometimes gory imagery to shock people. And I think it makes most people want to turn away rather than engage with your issue.”

What effect do the images we use have on our audiences?

This conversation got us thinking at Animal Think Tank, and prompted a message-testing study we did on visual imagery with short slogans. The study involved two phases. First, we tested messages with 'nightmare' images of animals trapped in factory farms versus messages with 'dream' images of farmed animals living in sanctuary (or the false image promoted by Big Animal Ag). Finally, we tested messages that contrasted a 'nightmare'/'reality' image with a 'dream'/'myth' image.

The results?

Messages with images that just showed the ‘dream’ were least effective at persuading people to take some form of action.

Messages with images that just showed the ‘nightmare’ were slightly more effective.

However, messages that had two contrasting images of nightmare/dream or reality/myth were most persuasive.

While a message that only focuses on the vision is not enough (as there is no sense of moral outrage or urgency), we also found that messages that only focused on the problem were not as effective as a message that had both elements of the problem and the dream. In short, people need to understand the gravity of the problem, as well as understand what the vision of a better future – where other animals are free and thriving – really looks like. If we’re not communicating the vision, we’re failing to persuade those who could be persuaded.

At this year’s VARC conference, Melanie Joy also spoke about our movement’s focus on exposing the horrors of how animals are exploited, and how this can have a backfire effect. If people who don’t want to see graphic images are confronted with them, the messenger is seen as the ‘perpetrator’, rather than those who are inflicting the violence on other animals. More than that, by exposing non-consenting people to graphic images, we can make them feel threatened or fearful. And when people are in this threatened fight-or-flight mode, they are primed to put self-interest above considering the experiences of others. In short, this means their capacity to empathise with others becomes drastically reduced.

As Thomas Coombes, founder of Hope-Based Communications and former Head of Brand at Amnesty International, says:

“I realized that much of the urgent, crisis-driven, fear-based communication in human rights work might not be priming people for the response we want. Instead of fostering hope, agency, and empowerment, we may be reinforcing fear and self-preservation.”

Are we stripping away fellow animals’ dignity by casting them as the ‘victim’ in the story?

Eighteenth century philosopher and social reformer, Jeremy Bentham, famously said of other animals:

"The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?"

It was a powerful argument and one that reinforced the concept of animal welfare. But three centuries later, are we still too focused on exposing how other animals suffer, rather than showing how they can thrive?

As animal allies and social justice communicators, we need to be mindful of how we frame our animal cousins, and what effect this has on people’s ability to empathise with them. While we absolutely need to expose the reality of their situation (the ‘nightmare’), if we’re not also showing how they can thrive (the ‘dream’) and how they are unique individuals with personalities, emotions, likes and dislikes that are similar to humans, we’re not showing who they really are.

If a person is only exposed to images of pigs looking dirty and sad in factory farms (or even if they only see industry images of pigs who look supposedly happy being farmed), they are not seeing how they might love to run, or play with their friends, or eat their favourite foods, or avoid walking in puddles, or resist their confinement. They either see a ‘victim’ or they see a stereotype.

Fortunately, there are some stories that disrupt these harmful narratives of pigs as ‘dirty’ or ‘happy to be farmed’. Such as the fictional film Babe (about a pig who doesn’t want to be a farmed pig); the Oscar-nominated documentary Gunda; the real-life resistance story of Matilda, who escaped from a farm and gave birth to her piglets in nearby woodland (prompting a public outcry for them to be taken to sanctuary rather than slaughter); and internet sensation Esther the Wonder Pig, who showed how pigs are no different to dogs in all the ways that matter.

Stories that evoke empathy rather than sympathy

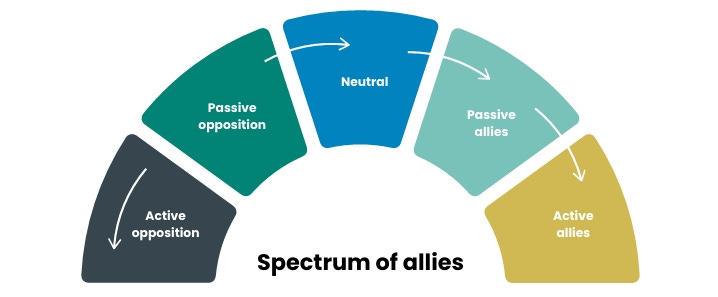

When we’ve spoken with animal organisations and asked what messages receive the most positive engagement on their social media, many are quick to tell us that messages that expose cruelty and abuse will lead to more supporters taking action and making donations. The reason for this is because their supporters (i.e. our movement’s passive or active allies - see graphic below) already feel empathy for farmed animals and so feel moral outrage at their suffering.

But people who haven’t given much thought to animals who are farmed before (neutral allies or passive opposition) might not yet see them as unique individuals. Exposing them to messages about cruelty and abuse might, at best, provoke feelings of pity and sympathy rather than empathy or, at worst, prompt them to shut down completely.

While empathy is a connecting emotion, sympathy is a distancing emotion:

Empathy is feeling with someone. It means putting yourself in their place, understanding and sharing their feelings as if they were your own. It’s about connection and recognising our shared emotional lives.

Sympathy is feeling for someone. It means acknowledging someone’s suffering or struggle but keeping a distance from them. It often comes with a sense of pity or sorrow, rather than shared emotional experience.

Research shows that perspective-taking plays an important role in helping people move toward supporting animal freedom. A 2024 study by Banach et al. found that simply sharing facts about how animals are treated did not lead to meaningful change. In fact, only the versions of the intervention that included an empathy-based exercise, where participants were encouraged to put themselves in the place of the animals, resulted in significant shifts in both attitudes and behaviour.

While empathy fosters a sense of kinship and solidarity, sympathy can unintentionally reinforce separation or hierarchy. So, to effectively build support for animal freedom, we need to provoke empathy in our audiences, not sympathy. And part of that is through reinforcing persuasive narratives like Animal Abilities and Bigger Us (see our Narrative Change mini guide for more details), as well as framing other animals with dignity, not merely as victims.

Shifting the narrative from welfare to freedom

Our primary goal, as animal allies, is helping people to understand, respect and empathise with our animal cousins. We want to get people to a place where they feel moral outrage that other animals are being farmed, raced, and tested on, rather than merely feeling pity about their conditions or mistreatment.

As a society, we are deeply rooted in a welfare worldview. While it has increased public concern about the ways other animals are mistreated, it's a narrative that has been co-opted by animal exploitation industries, to the point that 'animal welfare' has become synonymous with 'farming animals', and is also used by the racing, zoo and pharmaceutical industries to legitimise their businesses.

'Animal welfare', as a narrative, doesn't accelerate progress towards animal freedom – it maintains a status quo where using other animals is acceptable, as long as they're treated 'well'. (NB. when we're referring to animal welfare in this context, we mean as a 'public' narrative, rather than an 'inside game' strategy to improve the conditions of farmed animals trapped in a cruel system, which is a vital strategy of our movement.)

We absolutely should expose the reality of how other animals are suffering due to oppressive systems and cruel industries. But to ensure that people feel empathy, and not just pity or sympathy, we can also show how other animals can thrive if they are free.

To move people further along their journey, as well as change the narrative context, we can emphasise other animals' abilities (their intelligence, emotions, personalities, interests, cultures, similarities to humans etc.), as well what our vision of animal freedom really looks like...

People remember Martin Luther King's ‘I Have a Dream’ speech for the dream (how African Americans should be thriving alongside white Americans), not for the nightmare (of how they're currently suffering).

We need both the nightmare and the dream as part of our story. But we also need to remember that it's the vision of a better future that most inspires and motivates people.

Want to find out more about narrative change for animal freedom?

Check out the latest edition in our mini guide series: Narrative Change, published in April 2025…

Great article! Will keep this in mind for future posts!

Great piece! I love this idea "we can also show how other animals can thrive if they are free."

I have been writing about the connection between pleasure, consent and freedom. If we fully embrace consent - for every body, and in all aspects of life - we increase pleasure potential exponentially. By taking ownership of our own pleasure and happiness, while not violating others, we can attain freedom for all - including ourselves, i.e. "self interest." :-) I would love to hear your thoughts on this pleasure angle.